Palm Springs High alumnus wins $800,000 MacArthur 'genius grant'

Jonathan Horwitz

Jonathan Horwitz

A Palm Springs High School alumnus has won one of the most prestigious fellowships in the world.

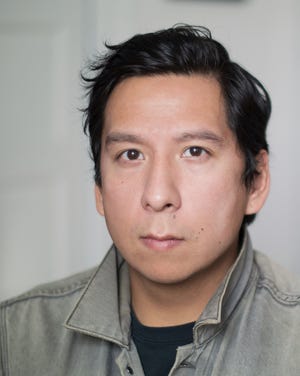

Sky Hopinka graduated from Palm Springs High School in 2002. This fall, he won the MacArthur “genius grant,” an $800,000, no-strings-attached award given annually to some of the nation’s highest-regarded creatives and scholars.

The stipend, to be paid over five years, is intended to provide seed money for intellectual, social and artistic endeavors, but there are no restrictions on how the money can be spent and no reporting obligations.

The whole process to become a MacArthur Fellow is a bit mysterious and rather opaque.

Fellows are nominated by an anonymous pool of professionals chosen from a broad range of fields and areas of interests. Finalists are evaluated by the foundation's internal selection committee based on creativity, accomplishments and potential to facilitate subsequent creative work and future advances in their fields. Recipients may be writers, physical and social scientists, artists, humanists, teachers, entrepreneurs or in other fields, with or without institutional affiliations. Fellows learn of their selection through a phone call from the foundation.

Hopinka, one of 25 MacArthur Fellows in this year’s class, is an avant-garde filmmaker dedicated to making new forms of cinema that center on the perspectives of Indigenous people.

Hopinka, 38, is a member of the Ho-Chunk Nation of Wisconsin and a descendent of the Pechanga Band of Luiseño Indians.

His films have been exhibited at the New York Museum of Modern Art and adulated by the New York Times.

“His work rivals in visual and linguistic beauty any new art I’ve seen in some time,” Times critic Holland Cotter wrote in 2020.

Hopinka is now an assistant professor of film and electronic arts at Bard College in New York, and plans to use the grant to continue filmmaking on his own terms.

His journey to the upper echelon of academia and visual arts has hardly been straightforward. It includes an adolescent chapter through the Coachella Valley where he was a self-described mediocre high school student and then a dropout from College of the Desert.

At age 12 or 13, Hopinka said he moved with his family from the Pacific Northwest to Palm Springs after his mother and stepfather took jobs at the Spotlight 29 casino.

Hopinka, whose films draw heavily on both natural and surreal imagery, says coming to the desert was transformative because he had never seen any environment like it.

His grandmother, a member of the Pechanga tribe, had lived in Southern California her whole life, but this land was new to him.

“Moving from that landscape of the Northwest to this landscape of the valley really gave me an appreciation of variations of the lands and different ways to identify with it,” he said. “I think that really prepared me for doing more of the movies and more of the traveling that I did throughout my life.”

Eventually, Hopinka returned to the Pacific Northwest to finish his bachelor’s degree at Portland State University and then moved to the Midwest to obtain his MFA degree from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee all before moving further east to New York.

Yet, Hopinka says the first move, the one that took him to the desert, was also the hardest.

At Palm Springs High, he didn’t stand out. And when The Desert Sun called the school district for a record of his attendance, there were no records to be found. (The district’s digital record system goes back to around 2003, one year after he graduated).

“I've always been one of the students that kind of slips through the cracks,” Hopinka said. “I just didn't like to cause any waves. I was pretty quiet. I didn’t take any AP classes or anything like that. I think it’s always a place of comfort for me just to kind of be a little bit invisible.”

He skated by in school without participating in formal extracurricular activities.

He never picked up a camera until he was 18 years old and took half a semester of black and white photography at College of the Desert.

Capturing his first images felt “exotic” and “foreign,” he said.

But the experience also empowered him.

“Wow, I can make an image. I can photograph this,” he recalls thinking.

Those feelings have stayed with him through his career.

Hopinka’s films sometimes appear exotic or unusual as overlapping voiceovers, natural sounds and nonsequential images flaunt standard filmmaking principles. His finished works have become empowering examples of Indigenous storytelling that question traditional power dynamics and biases in documentary filmmaking, Hopinka explained.

“Knowing that you can break the rules and you're asked to break the rules and question them, has really helped to help foster the kinds of films that I'm making now,” Hopinka said.

While his career might seem clear to him now, for a longtime between after taking that course at College of the Desert, Hopinka never imagined himself as a filmmaker.

He wanted to be a musician or some other type of creative.

“I thought I was gonna be a musician for a while. I thought I was going to be a sound engineer for a while. I wanted to be a writer for a while,” he said.

That “while” lasted several years and included phases in and out of college and times of racking up “a ton of student debt and credit card debt,” Hopinka said.

After his brief stint at COD, he moved to Riverside and took some courses at Riverside City College. But he didn’t graduate with his bachelor’s degree from Portland State University until about 10 years after he finished high school and years after he left Southern California.

Nowadays, he comes back to the Coachella Valley often to visit family.

“I think of the Coachella Valley as home in a lot of ways,” he said.

It was here in the desert through that uncertain period in his late teens and 20s where Hopinka began to find his path forward.

“I learned to drive in Palm Springs, and I think that driving down 111 or up into Santa Jacinto or just, you know, wherever on the highway just like really gave me an appreciation for the landscape, for the variation and also just finding beauty amid things that can be harsh and inhospitable at times,” he said.

It’s clear the motifs from those long desert drives have influenced his work. His 2015 film “Jáaji Approx” (Jáaji is a direct address form of “father” in the Ho-Chunk language) is set along an imaginary road trip in a car traveling across the American West.

Long before he made that movie, Hopinka purchased his first digital camera, an entry-level Canon.

“It would allow me to make films and not have to ask for a budget,” he said. “That’s how I started making films — on my own terms with a camera and a microphone.”

“The sort of feeling of being beholden to no one, to no funder or no producer, was really freeing,” he added. “I approach the films that I make now in the same sort of way.”

Whatever he chooses to film, Hopinka says he always tries to challenge himself with every project, including working through ideas in different ways while not trying to burden a single story with too many concepts.

To that end, Hopinka hopes his acclaim is just one step toward more opportunities for other Indigenous filmmakers to work through their ideas with support from major academic and artistic institutions.

“I don't want to be the token, and I don't want to be the one Native artist that is highlighted during November,” he said. “I want there to be, if anything, an invitation to look deeper into what Native peoples are doing now with cameras, with film and with art because that's important.”

Jonathan Horwitz covers education for The Desert Sun. Reach him atjonathan.horwitz@desertsun.com.